The right fit: housing for needs, not excess

Achieving EU climate goals, decent housing and affordable energy for all through sufficiency policies.

Our spaces are not reflecting our needs

We would not wear shoes five sizes too big, so why would we take up spaces beyond our needs and means?

Our built environment is a massive burden on the planet. In the European Union alone, buildings account for 50% of all extracted material and 40% of the energy consumption. Despite progress in reducing energy demand in European buildings, overall CO2 emissions per capita have continued to increase in recent years driven mostly by two trends: more consumption and demands for bigger buildings in some areas.

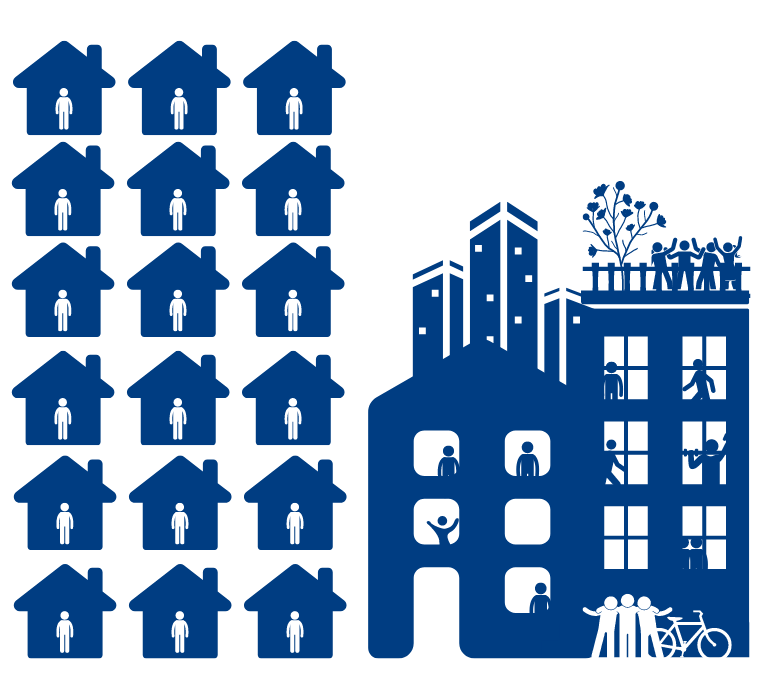

Residential floor area per capita in the wealthiest European Member States is well above the global average estimated in scenarios aiming at 1.5°C target, with many spaces under-occupied (e.g., offices that are only used half of the time). If we consider sufficiency policies to reduce space wasting and optimise our resources, emissions in the use phase of buildings of residential buildings could be significantly lower by 20250.

In a time where many struggle to afford a home and daily bills and planetary boundaries are stretched to their limits, we need to reflect how we use our built spaces, and how we can best match our needs within our resource budgets. We need sufficiency policies.

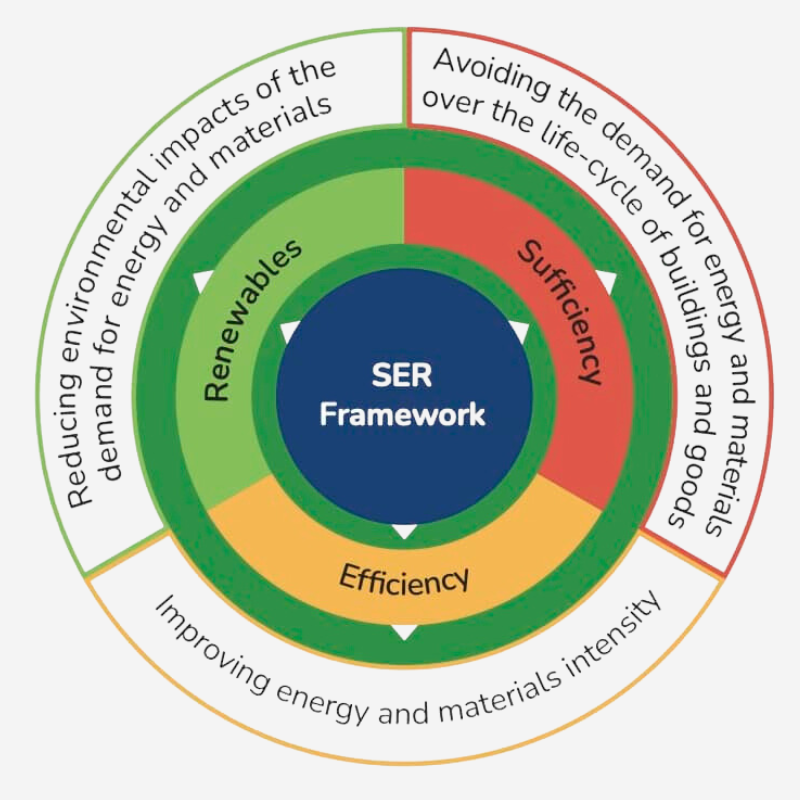

"Sufficiency policies are a set of measures and daily practices to avoid the demand for energy, materials, land, water, and other natural resources over the lifecycle of buildings and goods while delivering wellbeing for all within planetary boundaries."

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2022

Sufficiency vs. efficiency

From one way to optimise resources to another, it can be difficult to tell efficiency and sufficiency apart.

Efficiency refers to reducing the amount of resources used in the production, distribution and use-phase of energy and materials, whereas sufficiency refers to an absolute reduction in demand. Put into example, efficiency measure would be adding insulations to reduce energy bills, while sufficiency measure would be moving towards smaller and flex-work offices to avoid heating and cooling oversized and underutilised spaces.

Both concepts are key parts of the SER framework, the key to decarbonise our built environment.

While efficiency is essential, it cannot be enough to renovate the EU’s ageing building stock and improve their energy efficiency. The vast scale of the decoupling required, and the urgency with which it must be achieved, relying solely on one method to transition to a sustainable future is impossible. We must complement our renewable transition and efficiency policies with sufficiency, for reasons of both ecological sustainability and social justice.

It's not about having less

It’s about ensuring our wellbeing, meeting our adequate needs, all the while not breaking planetary boundaries when it comes to the natural resources (e.g. energy, land, materials) required to upkeep the lifecycle of buildings.

The sufficiency approach spans beyond behavioural change and may, for example, include occupying empty buildings, promoting shared spaces or just space allocation. One attempt to define the implementation of sufficiency in buildings has been formulated as “the adequate space thoughtfully constructed and sufficiently equipped for reasonable use”.

Sufficiency means that everyone can enjoy a decent housing, including the ability to afford the energy required in the buildings to cover the essential needs. Sufficiency measures mean further energy savings, in addition to those done through efficiency measures and the satisfaction of our needs through renewables. Together with circularity, sufficiency approaches have a huge potential to help reduce embodied emissions and ultimately decarbonise our building stock, as well as reduce the sector’s material footprints.

What do sufficiency policies look like?

Adaptable and flexible buildings

Example: Cohaus Kloster Schehdorf (DE)

Using empty and rundown buildings

Example: ShareHome (BE)

Monitoring

Example: Zwischenzeitzentrale (ZZZ) Bremen (DE)

Promoting shared spaces and services

Example: Agency for Building communities (DE)

Adaptable real estate sector

More on sufficiency

With facsheet, the EEB calls for a sufficient built envionment that will address Europe’s climate, energy and housing crises.

An overview of challenges in the social and economic foundation of European urban areas.

The paper outlines how more balanced, efficient space use represents a massive opportunity for wellbeing, climate mitigation and adaptation, and nature.

In the context of the development of the CLEVER scenario led by the negaWatt association, the authors establish a common vision on the residential sector bridging climate and social requirments.

Rue des Deux Eglises 14-16, B-1000 Brussels. Tel: +32 2 289 10 90 – E-mail: eeb@eeb.org. EC register for interest representatives: Identification number 06798511314-27

International non-profit association – Association internationale sans but lucratif (AISBL)

BCE identification number: 0415.814.848

RPM Tribunal de l’entreprise francophone de Bruxelles

Funded by the European Union.

The contents of this page are the sole responsibility of the European Environmental Bureau and cannot be regarded as reflecting the position of the funders mentioned above.